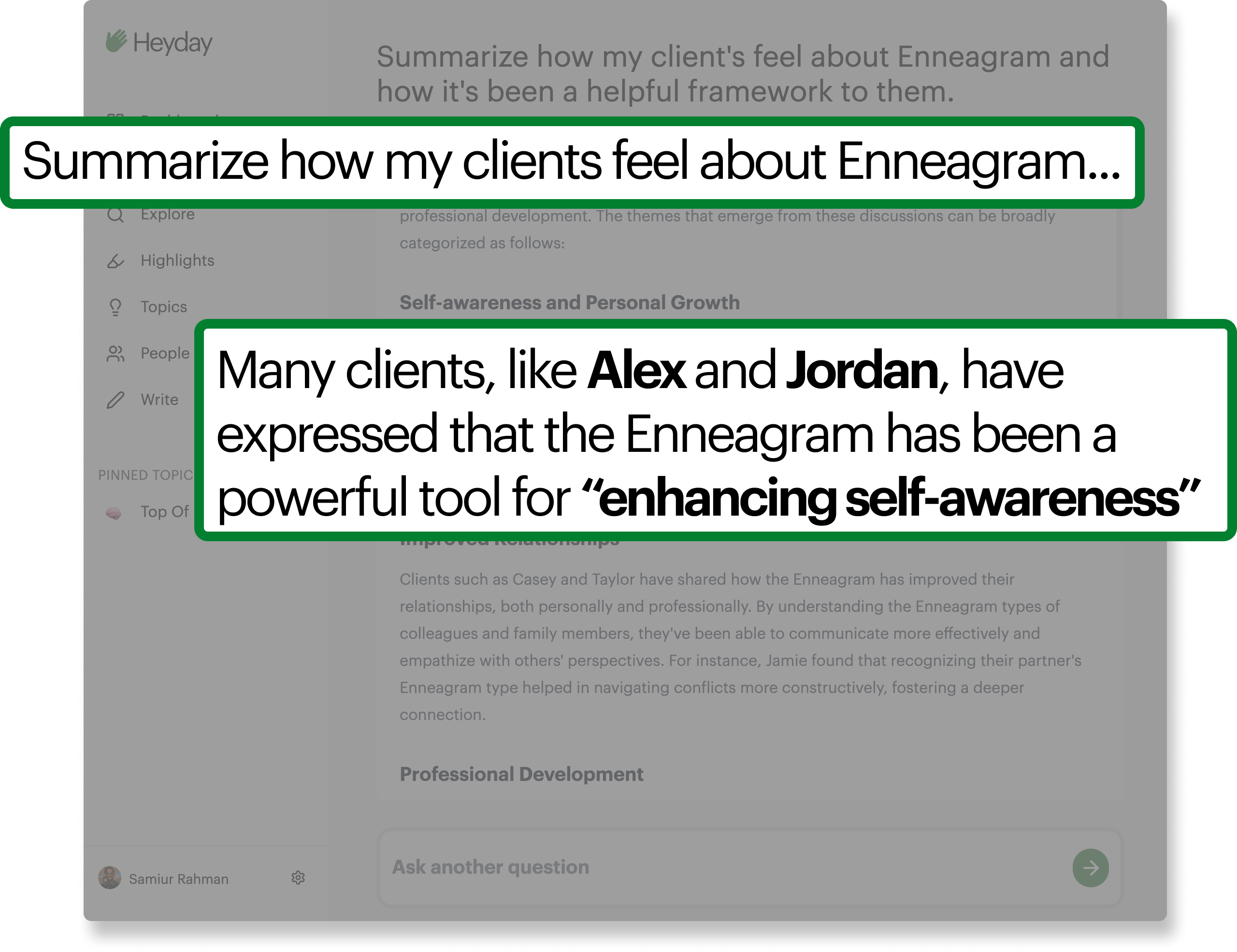

Let AI do the heavy lifting

Modern professionals rely on Heyday to generate meeting notes, extract insights from research, and draft content that draws from past reading and conversations. Here’s how it works:

Give your brain a boost

Extract insights from what you've written, read, and said

It's impossible to remember all the meaningful information you consume.

Heyday summarizes key points and answers questions, drawing from your emails, documents, notes, conversations, and articles.

Heyday is a badass product and you guys have been doing a fantastic job building it while listening to customers. I'm thrilled to support and advocate for it!

Brian Wang

Executive Coach, Dashing Leadership

.png?ixlib=gatsbyFP&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=max&q=50&w=5120&h=3940)

Tap into your wisdom (vs. ChatGPT)

Heyday is always learning more about me. It shows my writing from my documents within the posts it generates. That's really cool to see.

Justin Hills

Executive Coach, Courageous&Co

Draws from your conversations and notes

ChatGPT doesn't know you or your clients. Heyday creates a database of your wisdom based on your conversations, emails, documents, and notes.

No extra work

You can stop uploading transcripts into ChatGPT. The Heyday Secure Zoom App joins your conversations and generates notes with zero clicks.

Augments your workflow

Heyday goes beyond Q&A. It emails you call notes & new content ideas and shows you context about clients in your calendar - an AI that helps you wherever you are.

You're in safe hands with Heyday

100% Confidential

No one at Heyday can see your data. It is encrypted and will only be seen by others if you choose to share it.

Delete-able

You can delete your data at any time. Heyday deletes your data automatically when your free trial ends.

Verified

Heyday has completed exhaustive security reviews conducted by Zoom and Google.

People who do a lot of research love Heyday

Great product! Heyday is a fantastic support to coaching conversations both to remember what was said during the call and to prepare for the next conversation. I love how fast they ship things.

Erich Nussbaumer

Leadership Coach, Ayni Leadership

Heyday is creating efficiencies, ease, and more powerful engagement for me and my coachees. I'm able to listen more deeply because I'm not simultaneously typing up notes.

Julie Davidson

Coach, a)plan coaching

Some coaches are blessed with the ability to remember everything, others of us struggle. Heyday makes it easy to remember session themes, track action items, and organize my thoughts.

Dr. Matthew Jones

Cofounder Coach

Heyday is a badass product and you guys have been doing a fantastic job building it while listening to customers. I'm thrilled to support and advocate for it!

Brian Wang

Executive Coach, Dashing Leadership

As someone with a sloppy brain who spends a lot of time on the internet, Heyday's ability to organize everything for me is a life-saver.

Packy McCormick

Investor, Not Boring Capital

I love that it passively combs my history and contextualizes for me. In my case, I look at a lot of papers, and I'm always going, "where did I see that?" With Heyday I can quickly find it.

Noah Rosenberg

Founder, Sundial

I’m a long-time sufferer of ‘i read something once that said X’ then could never find the article again. Heyday fixes that and makes it easy to collate topics without having to manually tag every page.

Patrick Tomasiewicz

Comms Strategy, Anomaly

As part of my day job I go through 100s of websites every day and have to revisit many of them. Heyday has been a savior for me by surfacing the websites at the right time and right context.

Rohit Kaul

Research Analyst, Sacra

I've been using Heyday for a few months and it has done an exceptional job helping me resurface content without having to worry about saving, bookmarking, or keeping tabs open. Which is amazing, because I've been a chronic and incorrigible tabhog for years.

James Rosen-Birch

Founder, Stealth

Heyday is quickly becoming indispensable.

Nathan Baschez

Founder of Lex

My conversations with clients are highly confidential. There’s not a single product that I trust more than Heyday to keep them private and safe.

Ben Easter

Head Coach at Lucid Shift Coaching

Heyday improves my client satisfaction with minimal effort on my part. I especially value that it quietly captures shockingly spot-on notes for my clients. Keep up the good work.

Jason Pliml

Executive Coach, Inside-Out Leadership

I really love how seamless Heyday is to use with the Zoom app. There is like no setup. Thank you all for that.

Kelly Liu

Career Coach, Kelly Liu Coaching

Heyday hasn't just made me feel smarter, pretty sure it's made me smarter, or at least made future me smarter.

Erik Martin

Vice President of Services, Commsor

If I had one productivity tool to use for the rest of my days, and you made me get rid of all my others, I would be fine using Heyday.

Emily Weltman

Founder, Collective Flow Publishing

Heyday just works. I highly recommend it for anyone who has 100+ browser tabs open, is drowning in sticky notes (digital or otherwise), or needs to keep track of research information over time.

Shaun Nestor

Founder, Shaun Nestor Brands

As a product person and founder at a startup, I'm constantly reading up on our problem space and customers. Heyday ties it all together.

Chris Shilling

Founder, Driveway

I'm a big fan of Heyday. I've noticed that when my attention is completely freed up from taking notes I'm even more present with my clients and my powerful questions are a bit more creative and attuned. I believe my sessions have improved and it's a timesaver!

Marc Morin

Coach, a)plan coaching

I have been using Heyday in my coaching business and it is incredibly useful. My notes and prep process is now incredibly fast, and the coolest thing is that I can query my calls and notes for insights and content help.

Ben Easter

Head Coach at Lucid Shift Coaching

Heyday greatly improved my writing process. The summary of themes you identify based on last week’s conversations and suggestions for posts are awesome!

Bea Kim

Executive & Life Coach, Bea Kim Coaching

Heyday is always learning more about me. It shows my writing from my documents within the posts it generates. That's really cool to see.

Justin Hills

Executive Coach, Courageous&Co

The beauty of Heyday is that it works seamlessly alongside you without being annoying. When you go looking for it, it's loaded with incredibly useful content that makes life easier, smarter, and just downright enjoyable.

Jack Cohen

Vice President, FirstMark Capital

Heyday is a great product for creators and knowledge workers alike. It basically functions as an extension of my memory that's searchable, shareable & easily manipulated.

Kyle O'Brien

Founder, Startup ROI

Heyday was an easy sell: effortless bookmarks and contextual serendipity. I switched over from MyMind and haven't looked back.

Lorenzo Santos

Product Manager, ConsenSys/MetaMask

Slick! Particularly in the age of information overload when we forget what we read so fast. Love the resurfacing part - repetition makes the game.

Carlo Thissen

Founder, tl;dv

A copilot for all use cases

I've tried every Personal Knowledge Management tool possible and Heyday just blows them all out of the water. This is not an exaggeration.

Eli Velez

Marketing & Partnerships, Roc Nation